Arne Trageton

Stord/Haugesund College 27.7.01.

A preliminary draft

5409 Stord

Creative writing on computers, grade 1-4. Playful

learning in grade 2

The development for the 6 year olds in grade 1 is earlier described in

my presentation at ICCP in Germany (Trageton 2001) In this paper I concentrate

about the development in grade 2. The general description of the

total project, however, is almost identical with the start of the earlier ICCP

presentation. Thereafter this paper describes the development of the second

year in the three-year project.

Background

The computer revolution has changed

society radically the last 30 years. The computer is ordinary furniture at home besides TV and video for

70-90% of the 6 year olds in grade 1 in Norway. The children have been consuming a huge mass of TV, video and

computer games before starting school. But

computer based learning still play a minor role in the Norwegian schools. Our

Department of Education have now used a lot of money in material resources and

teacher courses to inspire the schools on all levels to more focus on

computer-supported and computer-assisted learning. In 1997 there were 30

students per computer in Primary/secondary School, in 1999 there was 15

students per computer, 2 computers as a mean in every classroom.

Computer-assisted learning is most

usual at university, high school and secondary school. In lower primary school

(6-10 year olds) “drill and practice” programs have been of some use. Erstad

(1998) concludes that most of the IT innovation projects in Norway use a

traditional view on learning, in contrast to the social- constructivist view in

our new National Curriculum. Such projects therefore have little relevance to

the local based, cross-subject learning our new National Curriculum from 1997

demand, because the program control the child, like the traditional teacher and

standard textbooks. In contrast a simple word processor program is an

open-ended tool where the student control the program. This is more in tune

with a modern social-interactionist view of learning. The children can get a powerful typewriter for production of own thinking and meanings,

instead of consuming the textbooks or adult constructed “pedagogic

programs”. IT changes to ICT (information and communication

technology).

The text program takes over as writing utensil instead of the feather

pen from the 1850, the steel split pen from 1920 and the ballpoint pen from

1950. I guess that outside school the main

advantage of the computer in society is in text production and reading, not

the more complicated use of computers. Computer writing on word processors is

the normal communication on most places of work today in contrast to the

dominating handwriting 60 years ago. When our grade 1 students leave our

compulsory school about 2010 the computer writing will dominate even more. The

necessary computer competence at that time we know very little about, but I

guess that a higher level of writing and reading will be a central factor to

construct own meanings in the electronic networks, and read and chose among the

huge mass of written information.

When the home and society outside school use the computer as a word

processor, why should not the 6 year olds start their school writing with print

letters instead of time consuming, imperfect handmade letters? In our project

we start the writing process on computers for the 6 year olds, and delay the

formal teaching of correct handwriting to the 8 year olds. For 6-7 year olds,

handwriting is a hard, boring and difficult technical process. One reason is

that the fine-motor skills are not fully developed at that age, especially

among boys. Using the computer as a word processing tool is better for children

(Keetley 1996). The children learn the same letterforms as they find in all

reading books. The children can therefore concentrate on the content in

their written message instead of the forms of the letters. The children are

learning more central things in language: To talk, to discuss, to write and to

read stories.

According to our new National Curriculum (L97), creative activities, play

and work shall be the dominant learning methods for the children. Already after

the first year in the reform, this was generally accepted in the schools in

Norway (Trageton 1999, Helming 1999,

Hagesæter1999)

Our

new National Curriculum (L97) order creative activities play and work as

main learning methods in the informal learning for the 6-10 year olds. This

means not “free play”, but the teacher should make good frames and a cultural

climate for structured play or learning-centred play (Moyles 1994, Trageton

1997). The Norwegian language curriculum is strongly inspired and influenced of

the creative writing didactical research in the Trondheim area (Moslet 1999,

2000), where oral language and dialogues have got a more important position,

and creative writing is knit tighter to the reading.

For twenty years my Workshop Pedagogy have

been practiced in the Norwegian Lower Primary School (Trageton 1994). This

pedagogy is inspired by The Laboratory School in Chicago from1896, (Dewey

1899), Integrated Day in England in the Primary Schools (Brown/Precious 1969),

Gardner’s (1983) multiple intelligences, and Eisner´s (1996) stressing the

different expression modes in concept formation. The children are representing

their experiences in different expressive languages: Constructive play,

dramatic play, drawing, writing, reading and doing maths around the same theme.

I found that handwriting was an insufficient and unpractical tool for the

little child to tell the long story about their experiences within the chosen

theme. After the computer revolution and the word processor the situation have

changed. Now you also can play easily with the letters!

The student start playing with the keyboard and produce an enormous mass

of letters and letter strings in a short time. He will quickly learn 20-29

letters (or the letters most useful for his thoughts). Later on his letter

strings can develop to millions of different personal texts in the different

genres, without being bothered by the technical problems with more complicated

computer program, often of less educational value for lower primary school.

Oral language, text creating and meaningful reading have a central place in our

new National Curriculum. The traditional focus on formal, mechanical training

in writing and reading without meaningful context is strongly reduced.

But our project is not only about typewriting contra handwriting. It is

not only better language learning. The 6-10 year olds in Norway have now an

excellent tool to document the quality on the total theme organised

cross-subject learning in lower primary school, where art activities, play and

work are the dominating methods (Trageton 1997)

Earlier projects done by my students in postgraduate studies for lower

primary school is the background for the project (Strand 1993), but these

experiences need to be documented and evaluated in a more controlled research.

My strategy is the opposite of the traditional practice in Norway where

handwriting is learned first, and computer writing comes later, perhaps in

grade 4.

Problems

1. How to use computer writing in language

learning for lower primary school?

2. How to build up a database on Internet of

the writings of the children through grade 1-4?

3. Will concentration on computer writing in

grade 1 and 2 and delay formal handwriting to grade 3 give better results in

Norwegian language?

Will that be true for both oral and written

expression, and for meaningful reading?

Earlier

innovations/research

Have computers in school learning effect? The consumer ideology.

In spite of 30 years innovations of computers in school, relatively few

evaluations of learning effects exist. Forman (1998) criticise strongly the

mindless “push and see” programmes without learning effect. Silvern (1998)

urges educators to resist using computers primarily for practice and didactic

materials, as trite electronic books and meaningless electronic drill- and

practice worksheets. Surfing on Internet, where 95% of the information is

commercials, may end up in wasting time, doing surfing and learning nothing

(Wilson, 1997/98). The Observer 24.10.2000 are referring from an international

research group concluding that especially programme packs with computer games

and CD-rom for young children are destroying creativity. In Denmark Larsen

(1998) criticise the similar “pedagogical programme packs” to be useless,

old-fashioned, behaviouristic pedagogy in modern, electronic package. He regard

only simple tool programmes useful for learnin

Healy (1998) has 30-year background for computers in school. She is

scared of the blind beliefs of the worth of computers in school, and sums up

varied reports about misuse of computers in schools overall in US. She refers

to the reactions from therapists who warn against the damages on small children

with one-sided consuming of adult controlled computer software, both at home,

and now also an expanding area in school. This is like multiplying hundreds of

TV channels, where the ”push and see” syndrome, and the switching from one

channel to another destroy the concentration of the children. This tendency

becomes strengthened in so called “pedagogic program packages” of

behaviouristic type. Healy says she would not recommend to spend time at

computers before 8 year olds, because it take time away from more valuable

activities, where concentration is trained, for instance in a long-lasting

constructive or dramatic play. However, heavy advertising of commercial “play

and learn” programmes make just such programme packs common in preschools and

lower primary schools, also in Norway.

Healy has found rather few evaluations of learning effects of computers

in schools, and she refers to different authorities questioning the validity of

many of these evaluations. Much of the research is sponsored by IBM etc. and is

made of “computer people” and school

bureaucracy interested in good evaluations. In spite of Healy and others sad

results, the government, politicians, parents, and of course computer industry,

TV stations and commercials all believe that computers in schools are

necessarily good for modern learning.

The child as consumer of pedagogical programmes has been

dominating many of the innovation projects. According to Healy the most serious

problem is that the huge investment in computers, give very little money and

interest left for other valuable area of school, for instance further education

of the teachers, the arts, play and books to the libraries.

Conclusion: Though the heavy advertising for such “pedagogic programme”

packs love the word play, in my opinion this is very far from the spirit of

play, where the child have the control.

Children as producers. The computer as a tool for creative writing.

In Norway the Department of Education have funded a long row of

innovation and research projects. Now they are trying to inspire to projects

with a more social-constructivist view of learning (Vygotsky 1978, Lave/Wenger

1991) where the child produce and construct his own knowledge together with his

classmates as a common learning society (Ludvigsen 1999). Stord/Haugesund College is a national centre for use of

information technology in learning. The department have funded a

large project about computer based learning for our teacher students

(2000-2003). The most important principle is simple; to use the computer to

better written communication by knitting practice, theory teaching on campus,

and own studies more together (Engelsen/Eide 2001). But Norway has few projects in lower primary school, and almost

none about creative

writing in lower primary school! (My project has been funded partly from the

Department of Education, but mostly from Stord/Haugesund College).

Also internationally, there is surprising little research in this

special area. For example in ERIC, the well known pedagogic database, I found

60 000 projects about computers in school, about 20 000 in primary school, but

the combination «computer projects + primary school + writing» gave only

115 projects! Only 20 of these were for the age group 5-9 years. None of these

had any contact with play research! I think that some explanation might be that

the computer specialists are more interested in complicated use of the

computers, eventually “playing” with complicated technology, and the teachers

in lower primary school are more interested in the traditional handwriting than

computer printing for 6-7 year olds. A

lot of the 20 projects were related to the huge efforts made by WTR (“Writing

to Read”) projects in many American States the last 15 years for the 5-7 year

olds (for instance Willovs 1988, Chambless & Chambless 1993, Driscoll 1997,

Singh 1997). My pedagogical view is quit similar to WTR. I believe like Chomsky

(1982) that writing is easier than reading for most of the children. Therefore

writing should come first. Through their own writing, the children also read

and reformulate their own thinking. They learn reading through their own texts.

Later they can also read and understand the thinking of other people in

different types of picture/reading books.

But in contrast to WTR, teachers and children in my project are

stimulated to use a more playful and informal approach to learning. WTR have

also a much more complicated and costly technology than my project. We use old

computers of different types, only with a text program. Therefore the schools

get these computers very cheap or free. For the producers of computer hardware

and software there is of course no business in using old, recycled computers

and simple text programs. Maybe

therefore they show little interest in research of my type.

Play – Writing - Computers.

Quite opposite the “child as consumer” attitude, a main characteristic

of play is the child as culture producer (Huizinga 1938, Sutton Smith 1990).

But there are relatively few research projects about play in educational

setting in Primary School (except for instance Hartmann 1988, Hall & Abott

1991, Moyles 1994, Pessanha 1995, Trageton 1997, Lillemyr 1999) In US there is

a long tradition for combining play and early literacy. Christie /Roskos (2001)

makes a fine overview over the American research the last 10 years, and place

them in a piagetian, vygotskian and the latest within an ecological frame based

on Bronfenbrenner. Their view corresponds with the total learning climate I

want in my project.

But what about computers? Will computer consuming only take time and

energy from the more valuable play and learning activities? The big quantity of

technological computer research projects in school in US is dominated of a

consumer ideology. Rather few give an

analysis about the relation to early literacy and play. But Liang and Johnsen

(1999) give a good review over the relation between technology - early literacy

– play, and conclude that computer software may give valuable development and

learning for the 5-8 year olds also, if the children become producers in

tune with play criteria:

- Positive

affect

- Intrinsic

motivation

- Process

more important than product

- “As

if” or non-literal attitude

- Exploration

I would add that for the 6-10 year olds not only the process, but also

the product becomes more important for a long lasting high quality play

activity (Trageton 1997, 2001). They have following demands to software:

- Open

ended problem-solving oriented

- Developmental

appropriate in practice

- Strong

relation to play

Among very few programmes filling this criteria is tool programmes like

simple word-processing most important. Here the children have billions and

billions of possibilities to variable combinations and messages by only pushing

29 letters! In the same research group Youst (1998) stimulated the 5 year olds

in kindergarten to produce multimedia books and e-mail in a playful way with

drawing- and writing programs to develop communication ability. In the Nordic

countries Nielsen (1998) have for 10 years worked in a similar way with playful

activities in the Danish PEPINO project for 6-year olds in kindergarten. In

Sweden Klerfelt et al (1999) have concentrated on the producer role and

playful activities. But these experiments demand more complicated and costly

equipment, and the child needs more complicated training before he can control

the expression and communication of his meanings.

My intentions are to develop a simple low-technological, cheap, playful

learning strategy for writing/reading in the ordinary schools in Norway.

Engelsen/Eide (2001) stress ICT as catalyst for connection and communication

between teacher students. The same goals are central areas for my 6-10 year

olds.

I also try to map the development of spontaneous computer writing

among children (Schrader 1990) and compare with the better-established research

in the development of spontaneous handwriting (Sulzby 1997, Christie

1999).

Project description (1999-2002)

Ten classes (6 year olds) in different parts of Norway, three in

Denmark, one in Finland and one in Estonia started in the project in the fall

1999. I follow these children for 3 years. They have in their classrooms 2-10

recycled, cheap or free computers, where only word processing is possible. The

schools got old computers from firms, from community and from parents. All

writings shall be done in printed letters. Formal handwriting, usually taught

in grade 2 in Norway, is delayed to grade 3. Our assumption are that the

children then will learn formal correct handwriting much faster than in grade

2. We spare time to more important areas in language education.

There should always be two children together on each computer. This will

stimulate oral language and discussions, helping each other with technical and

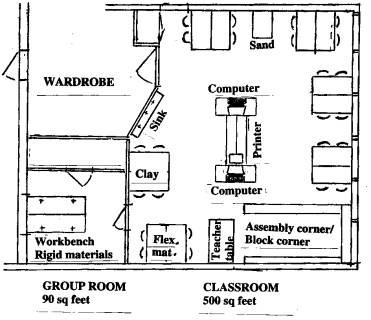

writing problems. Beneath I show one example of a classroom with only 2

computers placed in the middle of the room.

Here 4 of the children can use the computers at the same time. The rest

of the class is divided in small groups in corners suited for theme work and

play.

Fig. 1. Classroom organisation

Fig. 1. Classroom organisation

They can play with clay, sand, blocks, rigid and flexible materials in

the different corners (workshop pedagogy), they dramatize with their

constructions, they make drawings, and use the computers when these are free.

Classrooms divided in play/work corners are important for more informal,

playful education. Earlier research showed 50% more theme work and play in such

classrooms than traditional arranged (Trageton 1999)

Methods.

Documentation

The project is both descriptive and action research oriented (Elliot

1993, Mac Kernan 1998). Therefore the structure is relatively loose and open

ended. We want to describe the learning processes to develop practice more in

tune with our National Curriculum.

Problem 1 (see page 2).

Continuous process evaluation/discussions through 3 years in

collaboration with the teachers in the innovation classes. Observations,

notebooks/evaluations, interviews, video recordings and video productions of

theme organised learning with focus on the resulting text productions on

computers. Quantitative and qualitative analysis of the development in the text

productions of the children.

Problem 2.

From grade 1 I have scanned 1500 texts/drawings to build up a growing

database classified after school, grade level, sex and each student given an

identification number. This database is

on Internet, but at the moment only open for the members of the project group.

Later it may be opened for all interested in the project. In summer 2001 I have

scanned in all the texts from grade 2. Finally in summer 2002 I scan all the

texts from grade 3.

Problem 3.

Tests on language level after 3 year in the “experiment” classes and “control”

classes. The big problem is that there is not developed valid tests or

evaluation norms on the quality of oral language, written language and

meaningful reading developed in relation to the demands in Norwegian language

learning in our new National Curriculum for grade 1-4. Such tests/norms ought

to be developed, especially writing tests.

Qualitative

results in grade 2. Some examples

Grade 1 background

As a background I first take a quick revue of the development in grade 1

(Trageton 2001). In grade 1 the children in all classes started

spontaneous playing with the keyboard, and producing masses of letter strings.

Some meaningful words and sentences with invented spelling emerged. In the end

of the school year it could develop to small stories. In this informal way,

they had really written themselves to reading like in the American WTR

projects. The letter tests in the end of grade 1 told that most of the children

now mastered most of the letters, a mean of 24 capital letters and 20 minor

letters. The girls showed a bit higher scores than the boys. This is a higher

level than the results of Karlsdottir (1998) who followed the same children

from 7 year olds to grade 4 in reading capacity. Her conclusion was that the

most important factor to predict reading level in grade 4 was the knowledge of

letters in the start of school (at that time 7 year olds). The enormous

production of letter strings on the computers in grade 1 has really taught the

children “to be acquainted of the letters in their own individual speed” (L97:

117). Our National Curriculum says that in grade 1 the children should meet

letters and texts in written language through stimulating dramatic play and a

lot of picture/textbooks, and get help to write down their thoughts. It is very

informal demands in grade 1. The formal reading /writing is expected to wait

until grade 2. But “The computer kids” had already in grade 1 written small

texts in invented spelling, assisted by the teacher. They had been writing

themselves to read too early!

The start period in grade 2

The start period of grade 2 became therefore radically different from

the tradition with a common textbook for the whole class, learning one and one

letter at the same time, and formal hand writing exercises. It became

meaningless to follow a common textbook, where it is supposed that all children

should “learn” one and one letter at the same time, when my letter test showed

that most of the children already had learned most of the letters! On the

schools where the tradition was a common textbook in grade 2, this became a

great conflict, but most of the schools did not use a common textbook. Here

there were no problems. The formal reading/writing in grade 2 became

unnecessary and could be heavily reduced or skipped, because most of the pupils

could already write and read small texts based on the local environment

(situated learning Lave/Wenger 1991). The children simply continued writing and

reading on very different levels. Children learn to write by writing, to read

by reading. Quantity training is the keyword. In most classes the joyful

writing and reading interest exploded in the beginning of grade 2. The children

should not be disturbed by the same boring standard exercises for all students

at the same time.

Standard textbooks and workbooks are stealing time from meaningful

writing/reading in the language lessons. At the letter test in the end of grade

1, the children new some fewer minor than major letters. But now the small

letters became most interesting. Why? “Capital letters are childish” “Real

books use minor letters” “Minor letters

is harder”. This was some of the answers from the children. With help of Cap

Lock and Shift it became easy to convert letters from capital to minor letters.

A September example

Now I will give a glimpse from one of the classes after a month in grade

2:

The classroom is described on page 6. The recycled computers now with

only a text program installed, is bought from the community for about 100

dollars each. In my project the number of computers in classroom varies from

2-10. The mean in Norway will in 1999 be about 2 computers per classroom. With

such type of informal learning, when the main focus is on different group

works, 2 computers function well, but I regard the ideal would be 4.

23 students in grade 2 start their day with a quick briefing in the

assembly corner. The main matter is to discuss who should be the elected

represent ant to go to a meeting 0945. After that they were discussing their

theme for the period: I AND MY CLASS, and what the different groups have to do.

Then the groups begin to work/play in the block corner, with rigid materials,

clay, sand, drawing, playing with word cards, and 4 students in 2 pairs are

working on the computers in the middle of the classroom. Throughout the 4 hours

a day, computer groups are continually changing; so all the children have

written their stories at the end of the day. A sort of “Workshop Pedagogy”

(Trageton 1994) is practiced. The teacher has one assistant teacher 6 hours a

week. This resource is used this day. That is important to strengthen the

dialogue teacher /child, with the teacher as scaffolding the child

(Vygotsky/Bruner).

The theme “I and my class” fill 70% of the total lesson time in 1 ½

month. (According to our National Curriculum cross subject themes shall

dominate the learning in lower primary school). Just now it is the home arena

and the pets of the children in focus. An example of a developing text:

Kari and Truls are

working together. They have constructed a bed and a bird in rigid materials.

Kari still use major letters: IEI LAGET EN SENG (I have made a bed) Truls: Now

it is my turn. Kari: What will you write? Truls: I have made a bird. He looks

unsure on the keyboard: Kari helping: It begins with a straight line (pointing

at I). Truls writing: IEI (“I” in invented spelling). Teacher: What have you

written? Truls (reading) iei (I). Kari

helps Truls in sounding out: L-A-G-E-T (have made). Truls is writing with some

help of Kari to find the letters on the keyboard. Truls reading: I have made…

Kari: What have you made? Truls: Fugl (Bird). Kari: It begins with fffff

(sounding). Truls: lllll? Kari: No fffff! You find it about here: (Circling

movement over the keyboard F). At last Truls have written, “I have made a

bird”, and are reading aloud. Kari: Now it is my turn: She writes down while

reading what she is writing: “I was not allowed to play”. Truls: Were you not

allowed to play? Kari: No, when I had made the bed ready and should play with

the cat in the bed, then I was told to go to the computer.

This glimpse shows the importance of having pairs on each computer. The

children have an intense dialogue, are helping each other’s both with technical

problems, and in developing the content of the stories.

On the other computer another pair are developing longer stories of

their pets. Each child need more time, but the writing goes here faster, with

good responses from the onlooking and reading friend. The teacher may give

extra responses when necessary to enrich the story further. Nina have earlier

been in the drawing group and have made a detailed story of her smiling cat

with her grandmother patting the cat. On the computer the text to the picture

became such:

On the other computer another pair are developing longer stories of

their pets. Each child need more time, but the writing goes here faster, with

good responses from the onlooking and reading friend. The teacher may give

extra responses when necessary to enrich the story further. Nina have earlier

been in the drawing group and have made a detailed story of her smiling cat

with her grandmother patting the cat. On the computer the text to the picture

became such:

Fig. 2. Grandmother pat the cat

grandmother

pat

mia

mia smiling

soon healthy

she was

sick

she has

been bitten of

the

cat

Nina are reading aloud. The teacher do not understand here written

dialect version of “bitten” (bete). She

must read once more: Teacher understands: Oh, she has been “bitten” (standard

version). By whom have she been bitten? Nina: of the cat. Teacher

(encouraging): That you must write! Nina write “of the cat” and read the

story once more.

Her comrade Ida writes another story on background of her drawing.

Sentence after sentence is gradually printed down with encouraging response

from her pair comrade or teacher: What happened then? Why? What did the cat do?

What did you?

She reads the total story with much engagement, especially at

“nenenenenene” The teacher calls Kåre and ask him: Can you read the story? Kåre

quickly understand the context “pets” and is spelling slowly but correct until

the phrase nenenenenene… He sounds mechanical correct, but understand nothing.

Teacher: No, I think this Ida must read this!

Ida (with a teasing tone):

Teacher (enthusiastic): That was the teasing meaning!

Denmark, Estonia, Finland

The major part of the project is to follow 9 different schools in

Norway. But an interesting aspect is to compare with cultural variances in the

three other countries. Common traits for the three other countries are that the

6 year olds are preschool children and in the second year of the project they

had to shift institution to grade 1 in school (7 year old school start in these

countries). It was greater problems with continuity in the project, because

they both changed institutions and teachers. I have not so good documentation

from these countries, but here follow small glimpses:

Denmark

The new teachers had to build up the physical arrangements with

computers in the classroom. This technical equipment was not ready before

January in their 2 classes. Generally you will find a delayed development in

relation to all the Norwegian classes. Here follow one example:

Fig 5. Danish example

Fig 5. Danish example

ali baba andthe40 (robbers) once upon a time there was a poor

woodchopperas (invented spelling, not word division)

But in the end of grade 1 the two Danish classes had reached a

relatively high level, but not so freely experimenting as the Norwegian

classes. They were some more orientated against the formal aspect of writing.

Denmark has the last 2-3 year had huge discussions about the low reading

standard. Therefore the reading in standard textbooks has a very strong

position, and often also the free writing have the textbook as an inspiration

and starting point.

Estonia

One class is in the project. The class have few children, as a

combination of preschool class and grade 1. When I visited them to make video recordings

I got the impression of a more formal teaching than I was acquainted with from

Norway. But the teacher wanted to open for more creative learning methods. Here

follow an example of the text of a seven-year-old boy.

Fig. 6 Estonian example

Above is the teacher’s translation in English. The teacher had also

written the same story corrected to standard Estonian, so I notice that this

boy are quit near standard spelling. Only few places he uses invented spelling.

In relation to the other classes in the project, there is a very high

complexity in the Estonian stories. The teacher says that it is usual that the

Estonian children can read and write before entering school at 7-year age.

Finland

About 10 % of the Finnish people are Swedish speaking. The class in the

project is Swedish speaking. The preschool class should this year begin in

grade 1, in new localities, and a new teacher. But in this case the teacher

could continue, because she took a further education in lower primary school

pedagogic. She analysed 20 texts made in October in grade 1 (NB! like grade 2

in Norway). The texts were about children, families, friends, animals, friends,

fairy tale, and one text about war. The text length varied between 8-28 words,

the mean 18 words.

Because the child learn to write by writing, it is important to

stimulate the child to write longer texts by good questions like: What happened

then? Why? and so on.

Once upon a

time there was a pig named babe babe

went to eat babe eatsomuch

And babe

was fond of food that

he must go and laydown

In

bed and sleep with the teddy

This child use invented spelling, but relatively near standard spelling.

The teacher has in the red area at the left made a correct spelling of the

story. This is the child’s homework as a reading text. For the reading it can

be an advantage with such correction from the teacher. But it is important that

the child do not regard it as a criticism, only an adjustment to make the

interesting story easier to read, also for dad! These 2 pages can be the

beginning of an interesting book.

Newspapers

In the later part of grade 2 in the Norwegian classes, newspaper

production became exiting and very popular tasks. The typical tabloid newspaper

has short sentences, big titles and huge pictures. This is a suitable level for

grade 2. With computers as writing utensil the layout becomes more

professional, and the children have to discuss letter types and size. One grade

2 class in Bergen played a newspaper office for two weeks, with drafting

committee and groups of journalists who decided what stuff was important enough

to come in the newspaper: News, sports, production life, entertainment and so

on. At that time there was a great debate about a reality TV program named “Big

Brother” and some soaps with much sex and crime. Leading school directors

started a protest against these series competing with child TV time, and tried

to force the TV stations to delay such programs to late afternoon. The children

had in their newspaper to main news on the front page with drawings as

illustrations:

1) Hotel Cæsar (the popular soap program) must be sent later in the

afternoon

2) Eclipse of the moon

On page two the children had composed 5 different stories commenting

soaps and crime films. Her follows one:

Fig. 8. Newspaper article

Fig. 8. Newspaper article

Hotel Cæsar is not suitable

for children we in grade 2 are not

allowed to look at of mum and dad

I do not show the elaborated drawing to this text. Page 3 was about

sport, ski jumping, break dance and so on, page 4 presented constructions they

had done at school: We have made a globe, computers, TV, aeroplanes, space

rockets, etc. An article about the eclipse of the moon, a poem and a joke were

also written. The last page showed a weather report and different cosy stuff.

In my opinion the variation of this newspaper was better than our professional

tabloid newspapers in Norway! The newspaper had also a strong local touch

besides the national stuff. After printing 25 exemplar, the parents could buy a

very good newspaper to read in the weekend. Here follow the lay out of the

front page and page 7 in a 12 pages newspaper from another school. Different

journalists had created four different stories in pictures and texts: Boat

accident, train collision, school report and a football match. The front page

to the left had a short message about helping Brasil, as an invitation to read

a more elaborated article on page 2-4. It was info of a train accident, more

stuff at page 6, and a survey over the other content of the newspaper like

puzzles, jokes, comics and sport. The names of the journalists were very

important.

Fig.

9. Two pages from a 12 pages newspaper

Book production

To play a newspaper office with all different functions is a good way

for elder children to strengthen the “Literacy through play” strategy (for an

overview, see Christie 2001). Another good area strengthening literacy is

playing all the functions of a publishing house. Many of the grade 2 classes

have played publishing house the last part of the school year. To make longer

stories and write books with drawings and texts have become very popular

activities. A frame play (Brostrøm 1995) lasted for 2 months in one class

playing “Publishing house”. The teacher was the director of the publishing

house. She could be a very good consultant and critic of the first sketches of

promising books. She asked the author to elaborate the ideas of the good story

further on. She arranged conferences with all the authors who told each other

about their book synopsis and discussed how to improve them. They got

possibilities to test their sketches for other critical authors by reading

their ideas aloud for the total assembly. But the director also demonstrated

the high standard of the publishing house by denying to accept authors who come

with too little elaborated books. She criticized their manuscript for missing the

end of the story, or evaluated the front page not to be attractive enough,

discussed layout and size of the letters. After hard work on the criticised

areas, the director at last was willing to tape the logo of the publishing

house on the book as an acceptance of the finished book. It was amazing to

notice that the children accepted a rougher critic when the teacher was playing

the director role of the publishing house than when she was only their

classroom teacher! The books could vary from 4 to 20 pages, where the

illustrations were as important as the texts. Here follow one example:

1. Once

upon a time LITTLE BLUE 2.

Then LITTLE BLUE made an experiment he were sowing some strawberry made such as things

became small

seeds some

weeks after they began

to grow

experiment

all over he then there

were so big strawberries that he could live

became very

tiny. He screamed heeeeelp in the

strawberry garden so he ate and he ate until

but nobody

could hear it because he was he

became bigger and bigger at last he was

totally alone himself, and he would

not make it more for now he had stomach ache. THE END

Fig. 10. A storybook

What textbooks are

best for 7 year olds?

Traditionally formal reading in Norway has started for the 7 year olds

with ABC books (after lowering the school start this means grade 2). In

reaction against the rather meaningless technical texts in the dominating

phonic textbooks from the 1970ies, the modern textbooks have more “natural

language”. But this is the author’s natural language, not the child’s natural

language in a special class in a special environment. The problem many teachers

now report is that these modern, but foreign texts become too complicated, and

give no systematic phonic training or word recognition training.

By creative writing on computers instead of handwriting, you solve the

problem. The children themselves produce more interesting textbooks for

reading. By help of a scaffolding teacher they train themselves in systematic

spelling and word recognition while writing. After corrections to standard

spelling, the textbooks can be copied and supply every class with a mass of

interesting reading books from their own well known context, and therefore more

meaningful and easier understandable. In addition this should of course be

supplemented with a rich classroom library and school library for easy books of

professional authors on different content and levels.

Process orientated writing (is that a correct English term?)

The traditional writing of essays in high school and upper secondary

school were earlier made ready as homework without comments from the teacher.

The teacher assessed and marked only the finished product. A new orientation

the last 20 years have focused more about the process in the writings. (Healy

19?, Krashen 19?). The teacher follows the writing process and gives response

and advises to the student’s continual work with 1. sketch -> response ->

2. version -> response -> 3. version -> response -> final editing

(Hoel 1995). With younger children in grade 1-4, this strategy has earlier been

almost impossible. The motor problems with forming the letters take so much

energy, that the teacher could not demand the student to make a second version

of his text also. But with the word processor the situation have changed

completely. Children have quite natural given spontaneous responses to their

partner on the computer. The first sketch is easily revised to a better second

version. Clever questions from the teacher can expand the original version; the

child can make a new start on the story, or insert a forgotten important point

in the story, without writing the total text once more as in handwriting. At

last the child also can correct the spelling, make capital letters in the start

of new sentences etc. In working with newspapers and books the children get continuous

responses from their comrades, the teacher, parents and local society as

inspiration to revise their writings once more. How can the teacher reach

scaffolding 28 children in her responses? Here the pair group on each computer

is central for dialogues and oral development. The students become “assistant

teachers” for each other. Matre (2000) found that the dialogue between two 6-7

year old kids often had a higher quality than the dialogue child-teacher! This

oral dialogue function as an inspiring response. In grade 2, the teacher can

also give written response direct on the same computer (Hoel 2000:257-261)

Writing to Read – a revolution?

The traditional literacy training in Norway start not in writing, but in

the opposite end: Reading and reading problems were most in focus, often with a

special standard textbook with the same exercises for all children. The

traditional handwriting training was originally an own subject, isolated from

reading. The technical problems in copying letters were the main task. It took

therefore a very long time before the children could use these handmade letters

for expressing their own meanings in writing. Reading books had no connections

with writing books. They were regarded as isolated activities. (Lorentzen in

Moslet 1999:109-147). However, our new national curriculum (L97) demands a

closer connection between both oral and written activities: Combinations and

interactions between listening, speaking, reading and writing are highly

recommended:

Consumption Production

Oral: LISTENING SPEAKING

Written: READING WRITING

Oral language is strengthened in this new curriculum (Hertzberg &

Roe 1999). The children should learn language through oral and written

dialogues in a social interaction (Lorentzen in Moslet 1999:109-147). The left

side stands for impression or consumption, the right for expression or production.

“The students should every day talk

something that somebody listen to”

(L97 p 116)

Strong demands! Here production comes first, because the meanings of

every child is the most important, and easiest to start with! Active listening

can be harder for a 6-year-old, full of own interesting stories! In reading and

writing our new National curriculum focus more about the children’s production

of meanings. Creative writing has a dominating place. Such focus reflect also

that active writing of own text is easier than reading a foreign adult author’s

text. The revolution announced in the above heading is simply to revolve the

four components 180 degrees so the production components come first.

These components are easiest to learn in a playful way, because there is not a

single correct answer, but billions of different possible meanings.

Production Consumption

Oral: SPEAKING -> LISTENING

Such a strategy would correspond better with what we know today about

literacy learning.

Then it becomes easier to bind the four central components in literacy

together in an effective way. The child as active producer of knowledge

according to a social-constructivist view will be more visible. To write is

easier than to read (Chomsky 1982) Therefore we start with the easiest. The

reading research stresses the importance of decoding (Høyen 1996:223-234). But

in my project coding of own thoughts came first, and so decoding of the same

thoughts by reading them. This is easier than decoding foreign texts. But in

grade 2 it is also important that the children are training their reading

capacity on foreign texts. At first they read the books of their classmates

within the same local context, later on from the rich classroom library and the

school library.

Reading research has a hundred yearlong traditions, but it is only the

last 20 years that writing research has flourished. And still the reading

research gets most attention. While the international reading tests are

dominating the research and public discussions, we have almost no international

comparisons and public discussions about creative writing level.

Evaluation of writing level

Do the “computer children” write better than “handwriting children”? The

general impression from the teachers in the project is that the computer

children learned the letters in shorter time, and began to write meaningful

sentences earlier already in grade 1, and made better stories in grade 2 than

their classes they had before. In the end of grade 3, in May 2002, we also want

to make some more formal evaluation. But the problem is that there is no

accepted Norwegian or international evaluation instrument in this area. The

American Writing to Read project used different scales. One of them is the

following, where 6 was the maximum score:

- The

answer represents no understanding of the reading/writing process

- The

answer represents only an understanding of emergent writing.

- The

answer represent unclear, unimaginative writing

- The

answer represents understandable, but unimaginative writing

- There

is a visible main idea, but the organisation is weak with some missing

ideas or is not in proper order.

- The

answer is clearly organized and represent imaginative, interesting writing

( )

Brostrøm (1998) use another scale for the development of the oral

stories children create:

- Stories

with a bunch of not related sentences

- Stories

that are constructed by help of sequences, which partly are connected.

Focused chains

- Stories

with an elaborated structure. A logical relation between single sequences,

which gives sense to the whole, and with use of several roles, a number of

themes, and expressing a plot and with that using “the bridge of the

action”

- A

personal story

Can this scale also be used for written stories? Will the scale suit for

all types of texts, or only fabulous texts? Christie (1999, 1999b) has for many

years done much research about ”early

literacy and play”. His scale for narrative complexity of dramatic play builds

on Fein, Sutton Smith and Bruner. He use a more differentiated 6 graded scale

some similar with Brostrøm:

1.Thematic Event sequences

Incomplete Story Narratives

- Problem/

No Attempt

- Problem/

No Attempt/No Resolution

- Problem/

Attempt / Resolution

Complete Story Narratives

- Problem/

Attempt / Solution

- Problem/

Attempt/ Resolution Cycle

Can such a scale be used on children’s texts too? Only on narrative

stories? At Denmark Pedagogic University two researchers are working to develop

a writing test or evaluation instrument both for fabulous and factual texts.

Perhaps this is ready to May 2002?

Litteratur

Appelberg/Eriksson

(1999)Barn erövrar datorn. Studentlitteratur. Lund

Brostrøm S (1998) Children´s Stories and

Play. 8. European conference ECQECE Spania

Chamless J

& M Chamless (1993) The

effects of instructional technology on academic achievement of 2nd

grade students. University of Mississippi

Chomsky C (1982) Write now, read later. I Cazden (red)

Language in early childhood education. Washington NAEYC

Christie J et al

(1999) Enriched Play centre in Same-age and Multi-age Grouping Arrangements.

TASP New Mexico

Christie J et al.

(1999b) Play and early childhood development. Longman

Eisner

E (1996) Cognition and curriculum reconsidered 2. ed. Chapman. London

Engelsen K S & T Eide (2001) IKT som mediator for

refleksjon i studium og praksis. Paper NFPF Stockholm

Erstad O (1998)Innovasjon eller tradisjon. ITU. Universitetet i Oslo

Grankvist/Gudmundsdottir/Rismark(1997) Klasserommet i sentrum. Trondheim. Tapir

Gulbrandsen/Forslin

(1997)Helhetlig læring. Tano Aschehoug

Healy J M (2000)Tillkoplad

eller frånkoplad. Brain Books. Jönköping

Herzberg F & A Roe

(1999) Muntlig norsk. Tano. Aschehoug

Hoel T Løkensgard (1995)

Elevsamtalar om skriving i vidaregåande skolar. Responsgrupper i teori og

praksis.

Doktoravhandling AVH

Trondheim

(1999) Læring som kulturell og sosial

praksis. Norsk pedagogisk tidsskrift

6 s 343-

(2000) Skrive

og samtale. Responsgrupper som læringsfellesskap. Gyldendal Akademisk

Holm S (1988) Leselyst

og skriveglede. Aschehoug

Keetley EComparison of first grade computer assisted and handwritten process story

writing. Dissertation Johnsen and Wales Univeristy. USA

L 97 Læreplanverket for den 10 -årige

grunnskolen KUF

Larsen S (1998) IT og

nye læreprocesser. Eget forlag. Danmark

Lave/Wenger (1991) Situated learning - Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University. N.Y.

Lorentzen R Trøite (1996) Skriftspråksutvikling i

førskolealder.I Austad: Mening i tekst.

LNU. Cappelen

(1999) IKT

for dei minste. I Moslet (red) Norskdidaktikk. Tano Aschehoug

Ludvigsen S

(1999)Informasjons- og kommunikasjonsteknologi, læring og klasserommet. Bedre skole nr 2

Matre S (2000) Samtalar

mellom barn. Det norske Samlaget

Sandvik M et al

(2000) Resepsjon og retorikk. Prosjektbeskrivelse ITU. Universitetet i

Oslo

Schrader ( 1990) The Word

Processor as a Tool for developing Young Writers. ERIC ED 321 276

Singh B (1993) IBM’s Writing to Read program: The

right stuff or Just High Tech Bluff? ERIC ED 339 015

Strand K B (1993)

Datamaskinen i skrive- og leseopplæringa. FOU rapport Stord lærarhøgskule

Sulzby E(1990) Assessment of emergent writing and children’s

language while writing

I Morrow/Smith (ed) Assessment for instruction in early

literacy. Englewood Cliffs.

Strand K B (1993)Datamaskinen i skrive- og leseopplæringa.

FOU rapport. Stord lærarhøgskule

Trageton A (1995)Verkstadpedagogikk 6-10 år.

Fagbokforlaget

(1997)

Leik i småskolen. Fagbokforlaget

(1999) Tekstskaping på datamaskin 1. –4. klasse. Paper NFPF.

Kristiansand

(2000)Tekstskaping på

datamaskin 1.-4. klasse. NFPF kongress Kristiansand

(2000b) Tema i

småskolen. Fagbokforlaget

(2001) Creative writing on computers grade 1-4. Playful learning. 22. ICCP World Play conference. Erfurt. Germany

Vavik L (2000) Facilitating learning with

computer-based modelling and simulation environments. Doctoral

dissertation. University of Bergen

Willows D M (1988) Writing

to read as a new approach to beginning language arts instruction

Ontario

Institute for Studies in Education. Toronto

Yost N J Mc Kee

(1998) Computers, kids and crayons. Doctoral dissertation. Pennsylvania

State University.